The New York Academy of Art is pleased to share a new note by artist Hilary Harkness. “Notes from Studio Lockdown” is Hilary’s blog with us as she prepares for her upcoming exhibition in May at Mary Boone Gallery in New York City. Follow her on this blog for exclusive views of her studio practice!

Dear friends,

You might wonder why an artist like me, who paints imaginary scenarios, is a proponent of painting from life, but I do it quite regularly. I travel to significant locations to do preliminary studies from life to get a handle on how color behaves, I buy relevant props to paint to add touches of verite, and sometimes even ask my girlfriend to throw a right hook so I can depict a boxer convincingly.

On the other hand, I often make up color schemes that I use in a systematic fashion to make my scenarios seem real. For instance, I know blue light will create cool highlights and therefore the objects will cast warm shadows. I use the rule that highlights are sharper on shiny objects. I scour the works of Fragonard to try to guess at his color system. In addition, the journals of Eugene Delacroix are very useful because he described the exact pigments he used to create reflected light in the shadows of flesh.

| Hopper |

But here are three examples of why painting from life, at least at some point in your process, is unbeatable. In looking at the following paintings, let’s ask: Why is her face green?

| Hopper, detail |

A girl looks out from the shadows of her tenement window onto a bright snowy backyard scene. Looking closely, we see that her face has indeed been created using green paint. But in the context of the painting, it is obvious her face is not actually green. No color system in itself tells us why this use of green rings true. We can see from her rosy cheeks that her face is pinkish. If the local color of her face was yellow, then a reflected blue light from the snow could combine with that to make her appear greenish. Maybe the room she is in is green, but she is standing too close to the window for it to affect the appearance of her face. Perhaps the green skin is meant to make her cheeks seem an even more feverish bright red be contrast. The dullness of the green pigment (perhaps the earth color terre verte) makes her cheeks seem to actually radiate heat and light. It adds pathos: is this girl too sick to go out and play? Is she experiencing vicarious delight despite being at death’s door? The use of green in this girl’s face makes this painting transcend any illustration of a snowy scene, and I think this transcendence has sprung from years of observational painting.

|

| Van Gogh |

You would have to go to MoMA yourself to see that Vincent van Gogh uses green pigment in the flesh of his subject Joseph Roulin.Great painters don’t simply depict exactly what their eyes see like they are photographic machines; there is interplay between the artist and his subject, and the artist and his canvas.

Van Gogh has selected a limited palette and created a tight color envelope that allows certain greens to read as more neutral flesh-tones. In addition, the contrast of the even greener wallpaper behind Joseph Roulin pushes his face back toward a ruddy alcoholic complexion.

|

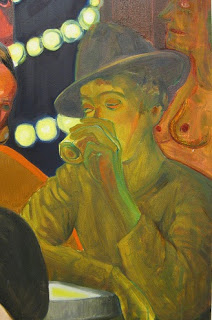

| Nicole Eisenman |

Nicole Eisenman has made many lovely paintings of scenes in nighttime beer gardens. She captures the conviviality of the moment, as well as the darker moments her characters could be experiencing. Eisenman is obviously a close observer of not only the unusual night-time lighting in this type of scene, but the varied emotions of the characters within them.

Yours very truly,

Hilary Harkness