Beautiful Beast

“Artists have a limited amount of studio time, so we have to be selective about which shows to see,” says Peter Drake, Academy Dean and curator of Beautiful Beast.

|

| During the Opening |

Studio Portraits: Hannah Stahl (MFA 2015)

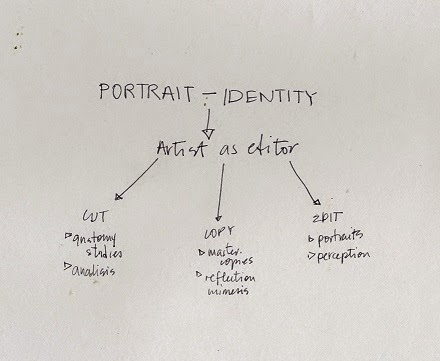

Beautiful Beast

Beautiful Beast, a group exhibition 16 acclaimed sculptors, explores the relationship between beauty and abjection through the lens of the grotesque with works by Barry X Ball, Monica Cook, Gehard Demetz, Lesley Dill, Richard Dupont, Eric Fischl, Judy Fox, Folkert de Jong, Elizabeth King, Mark Mennin, Evan Penny, Patricia Piccinini, Rona Pondick, Jeanne Silverthorne, Kiki Smith and Robert Taplin. Connected by their use of distortion to create fearless depictions of humanity, the work of Beautiful Beast runs the gamut of human emotion, often teetering towards the uncanny. Highlighting a wide range of work made over the past 20 years, the exhibition encompasses a variety of materials including foam, wood, steel and digital projections.

Curated by Peter Drake and organized by Elizabeth Hobson.

The exhibition is generously sponsored by Cadogan Tate Fine Art.

Exhibition/Artwork Inquiries: Elizabeth Hobson, Director of Exhibitions exhibitions@nyaa.edu (212) 842-5966

Media Inquiries: Folake Ologunja, PR Director fologunja@nyaa.edu (212) 842-5975

- Barry X Ball

- Barry X Ball

- Monica Cook

- Folkert de Jong

- Gehard Demetz

- Lesley Dill

- Richard Dupont

- Richard Dupont

- Richard Dupont

- Eric Fischl

- Judy Fox

- Judy Fox

- Judy Fox

- Judy Fox

- Elizabeth King

- Mark Mennin

- Evan Penny

- Evan Penny

- Patricia Piccinini

- Rona Pondick

- Jeanne Silverthorne

- Jeanne Silverthorne

- Kiki Smith

- Robert Taplin

Artist-in-Residence at Moscow 2015

During the summer of 2014 Sarah Issakharian (MFA 2015), Amanda Pulham (MFA 2014), James Raczkowski (MFA 2015) and Gabriel Zea (MFA 2015) participated in a month-long Artist-in-Residence Program in Moscow, Russia.

The Academy’s Residency Program is made possible by the New York Academy Travel Fund and the Villore Foundation. The Moscow Residency has been made possible through the efforts of Stephan Korsakov and Nikolay Koshelev (MFA 2014).

- Sarah Issakharian (MFA 2015)

- Sarah Issakharian (MFA 2015)

- Amanda Pulham (MFA 2014)

- Amanda Pulham (MFA 2014)

- Amanda Pulham (MFA 2014)

- Amanda Pulham (MFA 2014)

- James Raczkowski (MFA 2015)

- James Raczkowski (MFA 2015)

- James Raczkowski (MFA 2015)

- Gabriel Zea (MFA 2015)

- Gabriel Zea (MFA 2015)

A View From The Studios (Roll 2 / 2)

A View From The Studios

Roll 2 / 2

By Maya Koenig

|

Caleb Booth

MFA 2016

|

|

Tamalin Baumgarten

MFA 2015

|

|

Gabriel Zea

MFA 2015

|

|

Jaclyn Dooner

MFA 2015

|

|

Max Perkins

MFA 2015

|

|

Eric Pedersen

MFA 2015

|

|

Erich von Hasseln

MFA 2015

|

|

Alyssa Smith

MFA 2015

|

A View From The Studios (Roll 1 / 2)

A View From The Studios

Roll 1 / 2

By Maya Koenig

|

Self-Portrait on the 5th Floor

|

|

Jess Leo

MFA 2015

|

|

Moses Tuki

MFA 2015

|

|

Marco Palli

MFA 2016

|

|

Ciara Rafferty

MFA 2016

|

|

Gabriela Handal

MFA 2015

|

|

George Rue

MFA 2016

|

|

Kathryn Goshorn

MFA 2015

|

Stay tuned for Roll 2/2!

One Sweet World – Will Cotton Master Class

|

| Coconut Cake, 2013 |

Will Cotton stands before a medium sized canvas, blank but for a few brown marks he’s laid in for measurements. He lazily wipes his paintbrush on his apron, which was once white but is now splattered with brown and red paint. “This is my rag,” he tells us. His voice is clear and his manner relaxed, and although it’s Saturday morning, students hang on his every word. The apron, plus his thick-framed glasses and leather combat boots, lend Will a hipster-butcher look.

But Will is more of a baker than a butcher. He has created a world of dream-like, candy-confection-landscapes, often inhabited by human subjects, and is best known for his highly rendered oil paintings. However, his world extends far beyond the canvas. Over three weekends in November of 2009, he installed a pop-up French bakery/art installation at Partners & Spade, where he baked and sold confections that often serve as visual reference for his paintings. In 2010, he directed Katy Perry’s “California Gurls” music video, (again based around imagery from his paintings, which Perry was attracted to). In 2011, Will created “Cockaigne,” a scrumptious-smelling performance piece employing both ballet and burlesque to celebrate whipped cream and cotton candy.

Initially, Will strove to make art that came out of an awareness of the commercial consumer landscape we live in. He studied at the Academy in the late eighties, (when it was still on Lafayette Street), and after graduating began to develop a language in which the landscape itself – filled with candies and cakes – became the object of desire. In the early 2000s, nude or nearly nude figures began to populate these scenes. “These paintings are all about a very specific place,” he says. “It’s a utopia where all desire is fulfilled all the time, meaning ultimately that there can be no desire, as there is no desire without lack.”

|

| Will in his Studio |

He starts sketching out the model’s face and chest in raw umber, which he prefers as a drawing color because it dries quickly and is relatively transparent. “I like to compartmentalize,” he continues. “I put the structure down first, and then allow myself to move on to color… I think about John Singer Sargent, how he’d just kinda slap it on, and maybe be smoking and chatting while painting… I’m certainly no John Singer Sargent.”

“I begin with just the paint and turpentine because I don’t want it to get all slippery at the start,” he explains. At this early stage, he focuses on light, shadow, and contour, and is careful to point out that “contour includes the contours between light and shadow.”

As he draws, Will takes measurements and constantly corrects his work. “Drawing is all about being honest and not making assumptions. I’m always comparing between what I’m seeing and what I’m doing, and asking myself “what’s different?”” He pulls out a makeup sponge – “These things are great for erasing,” – and wipes away the lines of the model’s mouth. “It’s easy to think of the mouth as a flat structure, but we have to remind ourselves it’s curved.”

Most of Will’s paintings are very large, so a student asks how he draws out his compositions for larger pieces. “Usually I use like a 22×30 piece of paper and draw it out… and then I take a slide to project it,” he answers. “I cheat as much as possible…” He pauses. “Actually, I don’t think there is a cheating – the only thing that bothers me a bit is when I see people painting over photo printouts. There’s something I find a bit off-putting about that. But short of that, throughout all of history people have done whatever they can to get that image up there.”

I’m curious about how Will sets the rules for his world, so when he makes his way over to my canvas, I inquire about it. “Well,” he says, “The world I create is probably not a healthy one… It’s made of sweets, and humans live there, and probably die there, too.” Currently he’s gotten a little tired of painting nudes, so he’s been working on a lot of costumes. “I can’t paint people in regular clothes, because that wouldn’t make sense to me… So I’m painting costumes made of candy wrappers. I ask myself a lot of questions – would there be cellophane in this world? Yes, because candy wrappers are made of cellophane. Would there be cotton clothing? No. Burlap? Yes. I just make logical conclusions and follow a thread, and one thing leads to the next.”

Will’s Palette: (All Old Holland brand)

-Titanium White – for opacity and strength (usually for highlights)

-Magenta – (Quinecridone) – Will likes it for its coolness and vibrancy

-Cadmium Orange – With this and Magenta, you can mix any red you like

-Cadmium Yellow Light

-Delft Blue – this is a “middle” blue, so you can take it anywhere you want (ie towards green or towards purple). Will hates phthalos (monster-weed colors, far too strong), and ultramarine is too purple

-Ivory black –Will mostly uses the black for background, to represent a kind of dead zone or nothingness. Also, black and yellow make much more natural greens than blue and yellow

|

| The Deferred Promise of Complete Satisfaction, 2014 |

Many of us were surprised by the lack of earth colors (oxides, umbers, ochres) in Will’s palette, because his paintings contain a lot of browns and flesh tones. “I use oranges, blues, and whites to create my browns,” he explains.

Will spends a lot of time looking at the subtle differences in color across surfaces of skin. “Light on flesh tends to get cooler and greener,” he says, “so I often go for yellow and blue when going for light in the flesh.”

Perhaps the most important formula any Academy painting student will learn during their two years is this: when the light mass is warm, the shadow mass is cool, and vice versa. However, what really makes a painting “sing” is the subtle temperature differences in “reflected light,” within the shadow mass.

“I love reflected light. It’s just my favourite thing… What happens in between light and shadow – that’s what’s really interesting, what pays off – it’s more important than the color of the light mass,” he says. “See how this shadow color changes from blue to orange on the breast?” Considering how well-rendered Will’s paintings are, what surprised me most about him was his aggressive facture. “The great thing about doing an under-painting is that it preserves the drawing,” he says. With the drawing intact, he can absolutely attack the canvas when he introduces color. “I just put paint on and move it around until it looks right. I’m also not shy at all about taking it OFF.” He takes 3-inch wide bristle brush and pulls paint across the whole form. “I’m not a big believer in the sanctity of the mark,” he says, slashing through the paint he’s put down. He steps back to assess, and then lunges at the painting again, like a fencer. “You may mess it up by doing this, but it creates complexity. If you just blend along the line you get tubes and sausages. If you do it with a big brush, you get weird little skin-like things happening.”

Many times during my second year at the Academy I’ve been reminded to “cover my tracks” – that is, not let my viewer see how I’ve made a painting. A painting can lose some of its magic if the viewer can say “Here’s exactly how I would make that” and imagine themselves recreating the work. It was a treat to get an inside look at Will’s process, and to see just how he goes from blank canvas to his highly realized, dreamlike candy land. Will Cotton is a baker, a painter, and in this respect, a true magician.

COPY/CUT/EDIT

There is a process in which the artist’s identity inhabits the work one way or another. The real presence of identity is often overlooked. The Student Curatorial Committee (SCC) opened “Copy, Cut and Edit,” an exhibition that unveiled, through the practice of portraiture, the identity of artists with three different but complementary elements.

Curator Daniela Izaguirre stated that during the first month of classes she observed that many peers were finding personal insights through the use of techniques and methods assigned in class. For example, activities like analyzing our own facial anatomy that opened up internal dialogues with matters beyond observation. Then, realized there was a deeper story in the physical actions of creating artwork, a natural human narrative in making sense of who we are.

Richard Buchanan, a member of the SCC stated: “The student curatorial committee provides a wonderful platform for graduate students to engage with the curating experience. Being a part of this group has been a fantastic learning experience. I found Heidi Elbers’ (NYAA Manager of Exhibitions) input and guidance invaluable throughout the process.”

Curator Marco Palli reflects: “The best part of the curatorial process was to mingle with the student body. It was inspiring to see my peers’ work and to hear the stories and processes behind each single piece. I was honored that they let us enter into their studios. Unequivocally, I felt proud of belonging to this great community of artists.”

This exhibition is currently on view until late January 2015 on the 2nd and 3rd Floors at the New York Academy of Art. We invite you to experience it!

Artist-in-Residence Program at Leipzig 2014

During the summer of 2014 Matthew Comeau (MFA 2015), Esteban Ocampo Giraldo (MFA 2015, Fellow 2016), Camila Rocha (MFA 2015) and Hannah Stahl (MFA 2015) participated in a two-month Artist-in-Residence Program hosted by Leipzig International Art Programme, in Leipzig, Germany.

The Academy’s Leipzig residency is made possible by the New York Academy Travel Fund, the Villore Foundation and Trustees Gordon Bethune and Eric Fischl.

- Matthew Comeau (MFA 2015)

- Matthew Comeau (MFA 2015)

- Esteban Ocampo Giraldo (MFA 2015, Fellow 2016)

- Esteban Ocampo Giraldo (MFA 2015, Fellow 2016)

- Esteban Ocampo Giraldo (MFA 2015, Fellow 2016)

- Camila Rocha (MFA 2015)

- Camila Rocha (MFA 2015)

Cecily Brown in Conversation with Claire Cushman (MFA 2015)

People often tell Cecily Brown that she paints like a man from the fifties. Her response? “Well, somebody’s got to do it.”

Her large-scale, remarkably tactile oil paintings hover at the intersection between abstraction and figuration, and are often compared to Abstract Expressionist works. Based on the aggressive way she puts down paint and her star status in the art world, one might assume Cecily Brown would be a little intimidating in person.

|

| And you can see why I might be intimidated. (Cecily in Vanity Fair, 2000) |

|

| Don’t Bring me Down, 2011 |

|

| Brown in her studio

|