Camila’s Take Home a Nude

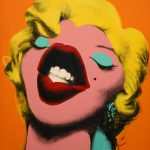

If you have no idea what Take Home a Nude is and the importance of this event let me explain. The Academy has many events throughout the year. Take Home a Nude takes place at Sotheby’s, a prominent auction house in Manhattan’s Upper East Side and each year many artists and students donate their artwork for Take Home a Nude’s silent auction.

If you have no idea what Take Home a Nude is and the importance of this event let me explain. The Academy has many events throughout the year. Take Home a Nude takes place at Sotheby’s, a prominent auction house in Manhattan’s Upper East Side and each year many artists and students donate their artwork for Take Home a Nude’s silent auction.

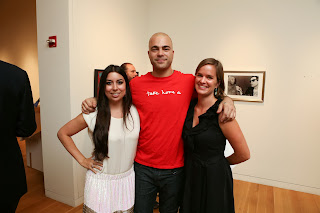

Events like these are very important for the future of the school thanks to the supporters and the generosity of the artists. We the students benefit from all the Academy has to offer. Current students and alums donate their time and work as volunteers, too. If you see a red t-shirt around, that is one of us!

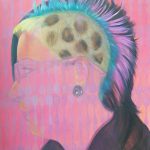

This year I had the opportunity to attend. The space was beautiful and the exhibited artwork was flawless.

This year I had the opportunity to attend. The space was beautiful and the exhibited artwork was flawless.

Talking with some of the New York Academy of Art’s supporters and patrons made me realize how serious they were about seeing our development. I felt truly motivated by their interest in our success. During our conversation they expressed how amazing the artwork created by the students were and how proud they were to see such quality work in the auction. It made me feel like I was talking with a family member.

.jpg) Just a couple of minutes after the opening, the room was filled with celebrities, models, art collectors, personalities from the worlds of fashion and design.

Just a couple of minutes after the opening, the room was filled with celebrities, models, art collectors, personalities from the worlds of fashion and design.

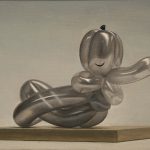

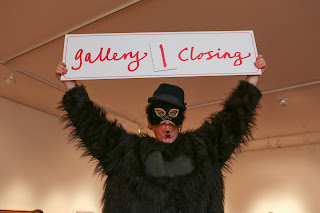

From room to room the silent auction took place and was filled with exciting moments before each hot lot closed. Each room had a few gallery sections, which were closing consecutively to their respective number, preceding the live auction.

The silent auction happened incredibly fast, and within a few hours all the walls started to be cleared, a sign of great success. Certainly those pieces found a new home.

By the last hour some of the artwork by renown artists went for live auction. This year we had works by Walton Ford, Cindy Sherman, Santi Moix.

I can’t wait for the next event. Its good to know as students the patrons and collectors have their eyes on us, watching our progress and looking for us to succeed.

Next post I will be introducing you to some of the Academy students and showing a little bit of the diversity the Academy has.

Camila Rocha (MFA 2015) will be blogging here throughout the year about her first year at the Academy and moving to New York City. Check the label “First Year Experience” or “Camila Rocha” for more posts about her first year at the Academy. If you have any questions for Camila, please leave them in the comments section of the blog.

All photographs taken by Nolan Conway.

Artist-in-Residence Program at China

During the summer of 2013 James Adelman (MFA 2014), Elliot Purse (MFA 2014), Elizabeth Shupe (MFA 2014), and Zoë Sua Kay (MFA 2014) participated in a eight-week Artist-in-Residence Program on the campuses of the University of Shanghai and the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. At the end of the residency all four artists participated in the group exhibition Mutual Interests Cross Culture Exhibition at the Fine Arts Gallery at University of Shanghai. This exhibition includes some of the work created during or attributed to their residency experience.

The Academy’s China Residency is made possible by the New York Academy Travel Fund, the Villore Foundation and Academy Trustee Gordon Bethune.

- James Adelman (MFA 2014)

- James Adelman (MFA 2014)

- James Adelman (MFA 2014)

- Elliot Purse (MFA 2014)

- Elliot Purse (MFA 2014)

- Elliot Purse (MFA 2014)

- Elizabeth Shupe (MFA 2014)

- Elizabeth Shupe (MFA 2014)

- Elizabeth Shupe (MFA 2014)

- Zoë Sua Kay (MFA 2014)

- Zoë Sua Kay (MFA 2014)

- Zoë Sua Kay (MFA 2014)

On View: Robert Plater (MFA 2013) with First Street Green

On a warm sunny day, I had the opportunity to watch Robert in action and talk with him about his experiences at and beyond the Academy. “Applying for the First Street Green opportunity was an easy 1-2-3 step process,” Plater recalled. “I had a food chain idea for the mural. I submitted my proposal, sent a drawing and link to my website and that’s was that. It was pretty easy”

On a warm sunny day, I had the opportunity to watch Robert in action and talk with him about his experiences at and beyond the Academy. “Applying for the First Street Green opportunity was an easy 1-2-3 step process,” Plater recalled. “I had a food chain idea for the mural. I submitted my proposal, sent a drawing and link to my website and that’s was that. It was pretty easy”

A few months later, Plater is now on site translating his design into a large scale mural. “Painting outside is a different experience. The visibility is unmatched. You are faced with many unique challenges and in many ways working against light and aware of its limitations. The noises are different. And it’s more interactive. I’m more excited to talk to people. The studio can be a chore. In this open space people don’t even ask to take pictures, it’s public so they feel like the art belongs to them. I get to do a lot of thinking out here, a lot of talking to myself. I feel more confident and less doubtful. “

Influenced by street art and graffiti, Plater came to the Academy with one goal in mind: He wanted to grow as an artist. He enrolled at the Academy to elevate his natural artistic talents and was attracted to the big names like Jenny Saville and Eric Fischl associated with the school. His goal of growing as an artist, however, was quickly put to the test by his instinct to protect himself.

Influenced by street art and graffiti, Plater came to the Academy with one goal in mind: He wanted to grow as an artist. He enrolled at the Academy to elevate his natural artistic talents and was attracted to the big names like Jenny Saville and Eric Fischl associated with the school. His goal of growing as an artist, however, was quickly put to the test by his instinct to protect himself.

Plater agrees it’s great to question the relevance of your work and be forced to push boundaries. In his work, he has applied the Academy’s rigorous training, teachings and references artists like Michaelangelo and Durer. When asked about his favorite classes, Plater talks about JP Roy’s class Painting from Imagination. “It felt free and inspired my confidence. When I was younger I did so much drawing that was simple by design and I drew from my head.

Robert Platers’ mural is on view until Jan 2013 at First Park, 33 E. 1st Street.

For more details on the artist take a look here Robert Plater (MFA 2013).

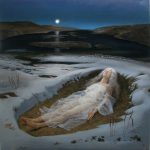

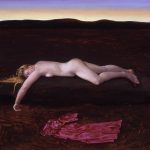

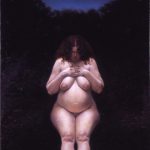

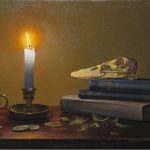

Martha Erlebacher Retrospective

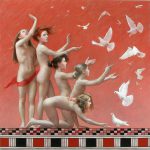

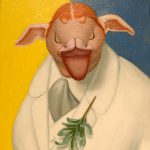

Trained originally in Abstract Expressionism, Erlebacher (along with her husband Walter) broke from this style in the late 60’s and quickly became recognized as one of the leading representational figurative and still-life artists in America. Erlebacher’s work examines the deep metaphorical and social themes of contemporary culture through her painterly and aesthetic images. This retrospective pays tribute to Martha’s outstanding leadership and tenure at the Academy.

This exhibition is presented in partnership with the Erlebacher family and Seraphin Gallery, Philadelphia.

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

- Martha Erlebacher

Artist and Teaching Residency for West Nottingham Academy – Part 2

By Jacob Hicks (MFA 2012)

By Jacob Hicks (MFA 2012)

West Nottingham Academy embeds its pupils in a program that teaches the values of creative art, exposing them early on to the richness of the practice. Students in my introduction to drawing-freshman and sophomores-mostly came in as clean slates, with little to no guided study. My task became setting a precedent of enjoyable learning. I wanted to make it rigorous yet fun so that the children might become converts to its ways and not end up with future disjointed memories of art fused with disinterest.

The first lesson, and one of my favorites so far, was a practical study in analytic and synthetic cubism. Cubism is a 20th century art movement, the visual equivalent of a parallel advancement in the sciences-relativity. Advancements rarely populate single territories, but spread across all of the humanities; there are cubist poets as well as modern authors who used verbalization to express similar revelations of the period, just in different mediums. To help my pupils grasp an abstract concept, I created a studio exercise. Each chose a partner and cycled between posing for and drawing one another for ten minute sessions. After one round the original pose was again taken, but each artist worked from a new viewpoint. This second perspective was layered upon the previous, thus illustrating multiple vantages of a single object, effectively fragmenting its stability. This is the nature of analytic cubism.

Each week we work on a new project, and included are pictures of some of the most successful works. (I have also included a photo of the painting I am making while my students work.)

My painting students have had more experience, being juniors and seniors who have taken several semesters of art. Most of them, however, have not had much experience with oil painting. I designed the course to teach the students the principles and craft of oil painting from start to finish, through canvas construction and surface preparation to indirect and direct painting application, all based on various modes of historical practice. The students work on a single composition throughout the course; so far they have created the surface-gessoed canvas on stretchers, composed the drawing, painted the drawing achromatically, applied generalized dead palate color, and are now working to finalize the image with multiple glazes and layers of full chroma. I asked that each composition include a subject and environment and elements of the imagination. This course is far-reaching in that it introduces and explains painting material and its history, the principles of design and composition, tonal structure and drawing, intensive color-theory, and the use of oil medium directly vs. indirectly.

Each student is asked to meet painting progression deadlines, contribute during critique of one another’s work, and present analysis on old master compositions of their choosing based on all of the formal, material, and historical information we cover.

We have a way to go before the class concludes with a student organized show in the school gallery, where we can celebrate everyone’s achievements. I must say, all the work is definitely paying off; I have included some shots of the paintings in their current states.

I am having a wonderful time not just teaching, but learning daily from my students. Each subject they choose to represent sets me on an experimental hunt alongside of them to find the clearest, most luminous way to embody it.

##Jacob Hicks (MFA 2012) will be blogging here throughout his artist residency at West Nottingham Academy, Colora, Maryland about his experience. If you have any questions for Jacob, please leave them in the comments section of the blog.

Artist and Teaching Residency for West Nottingham Academy – Thus Far

|

| Durga (in progress) |

Upon arrival in a lush rural landscape, overgrown with the stunning type of nature I didn’t yet realize I yearned for, I met Trish Kuhlman, head of WNA’s art department. Trish, an immensely talented painter and teacher, whose care for and responsibility to her students goes above and beyond the call, introduced me to faculty, staff, and students. Everyone showed (and continues to show) me such hospitality and welcome that I immediately became convinced I serendipitously turned up in some type of cinematic vision of paradise, where community is close and caring, where nature exhales a majesty that I then breath, where education unites and illuminates.

Upon arrival in a lush rural landscape, overgrown with the stunning type of nature I didn’t yet realize I yearned for, I met Trish Kuhlman, head of WNA’s art department. Trish, an immensely talented painter and teacher, whose care for and responsibility to her students goes above and beyond the call, introduced me to faculty, staff, and students. Everyone showed (and continues to show) me such hospitality and welcome that I immediately became convinced I serendipitously turned up in some type of cinematic vision of paradise, where community is close and caring, where nature exhales a majesty that I then breath, where education unites and illuminates. My father and I, elated and hopeful, unloaded the truck. Within the next two days we hung my show, the gallery being a beautifully open space in the main school building, and the proud owner of an authentic Foucault Pendulum, an early mechanical device that legitimized the theory that our Earth was in orbit (I could have believed the theory without the device, seeing as how my world never sits still for too long).

I fear the difficulty will now be for WNA to pry me loose at the end of my trimester, for I have fallen in love with this intimate, beautiful rural oasis.

##

Jacob Hicks (MFA 2012) will be blogging here throughout his artist residency at West Nottingham Academy, Colora, Maryland about his experience. If you have any questions for Jacob, please leave them in the comments section of the blog.

#2014Academy – First Year Experience Begins

Hello Academy Blog readers! As a first year student, I will be writing to you honestly about my experiences. All the affairs, fate, happiness and lovelessness of my current life, hopefully my view can give you periodically an idea of how overwhelmingly brilliant is to be a Master’s of Fine Art student at the New York Academy of Art.

| Old Masters Gallery at The Met |

| Greenpoint, Brooklyn art installation |

##

Camila Rocha (MFA 2015) will be blogging here throughout the year about her first year at the Academy and moving to New York City. Check the label “First Year Experience” or “Camila Rocha” for more posts about her first year at the Academy. If you have any questions for Camila, please leave them in the comments section of the blog.

All photographs taken by Camila Rocha.

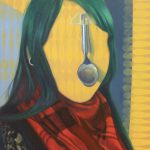

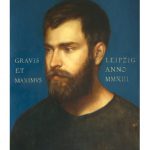

Artist-in-Residence at Leipzig

During the summer of 2013 Alicia Brown (MFA 2014), Tim Buckley (MFA 2014), Krista Smith (MFA 2014) and Shangkai Kevin Yu (MFA 2014) participated in a two-month Artist-in-Residence Program hosted by Leipzig International Art Programme, in Leipzig, Germany.

The Academy’s Leipzig residency is made possible by the New York Academy Travel Fund, the Villore Foundation and Trustees Gordon Bethune and Eric Fischl.

- Alicia Brown (MFA 2014)

- Alicia Brown (MFA 2014)

- Alicia Brown (MFA 2014)

- Tim Buckley (MFA 2014)

- Krista Smith (MFA 2014)

- Krista Smith (MFA 2014)

- Krista Smith (MFA 2014)

- Shangkai Kevin Yu (MFA 2014)

- Shangkai Kevin Yu (MFA 2014)

Meet the Academy Fellows: Nicolas Holiber (MFA 2012, Fellow 2013)

| Nicolas Holiber. Hero (detail), 2013. |

Nicolas Holiber: My name is Nicolas Holiber, I am 28 years old and I have an addiction to taking apart my sculptures. I was a Fellow for 2012-13 school year and now gearing up for the Fellowship show this September.

I met a guy last month and he was telling me there are two types of learning. One type is to learn through study; when you’re in front of a book. The other type is to learn through doing. My process is like the doing. I have to make something to figure out if I like it or not, or if it works. Even if I do a preparatory drawing, I still have to make it. Once I make it I can figure out if I like it or not and if I want to keep it that way. Most of the time I don’t. So I have to take it apart and turn it into something else.

|

| Studio shot courtesy of artist. |

Holiber: I guess I learn the form. I make a decision on what I want the form to be or not to be. If something is too recognizable, maybe I don’t want that, so I’ll make it simpler. What happens in that process is I start accumulating all these different dimensions, different aspects of the work: the writing, pieces of the wood get more interesting as they break off, the composition of the form might get a little more dynamic, so it really takes a lot of building and taking part to make something I am happy with.

Academy: Will you talk about the writing in your work a little bit? What that is and why it’s there?

Holiber: Before this guy was like this [point to “Hero”], it was more of a horse and rider sculpture. There’s a head over there that was the horse and he was the rider. They had this very rectangular and hollow body. In fact all these sculptures were hollow and they were very simple box torsos. The first one I made hollow by accident. I thought I should do something on the inside, the wood planks are all irregular so you could see the inside if you got close to it. I thought it would be nice if you could discover this whole other world as you approached the sculpture. So I did that to all the sculptures. And I painted them all white on the inside and I started drawing and writing in there too. It became kind of a diary, a visual and written diary. After I had finished doing that, I realized having the diary on the inside was a little too expected. Of course it would be on the inside of the sculptures because it’s a personal whatever. I thought the sculptures would be a little more dynamic if they had some of these painted and written pieces integrated into the form and composition of the sculptures, but not so narrative that you can go up to any of them and just read and understand it and where I am. This way it’s broken up and just gives little pieces and then the viewer can take away what he or she wants to. It’s also better for me because I am not completely out there.

My friend was telling me last night, she has a family tradition, what did she call it? It was “the Castles of Constraints.” Around Christmas time they make a castle out of boxes and wrapping paper. Everyone writes down their constraints and confessions and puts them in the castle. Then on New Year’s Eve they burn it. That is really, really interesting. It’s kind of similar to this where if it does get covered up, they’re in there and then they’re gone forever. The writing and the drawings in my work are just a lot of stuff that happened this year. Things in my life. Random stuff. My favorite book when I was growing up or other things that happened this year. It ranges from very personal to childlike.

|

| Studio shot courtesy of the artist. |

Academy: What do you feel when you look at these sculptures and your paintings?

Holiber: To be honest, when I look at my work I don’t really feel anything. I am just looking at things I should’ve done better. I want him to come across as hopeless [points to “Hero”]. Keep in mind he’s going to be paired up with a cast from the collection. You’re going to have these casts of immaculate sculptures that are the height of craftsmanship. I’ve been thinking a lot about why I wanted to use the Academy’s Casts so much and why I’m attracted to Classical sculpture, when I don’t want to make anything like that at all. I think it’s because when you see real Classical sculptures in real life it’s breathtaking. First of all, you know how old they are. I know how old they are in terms of years, but it’s hard to really understand their age. I think the reason I like those sculptures in particular is the effect of time and the brutality of history is so much more evident on sculptures than on paintings or drawings. There’s a brutality to ancient sculptures that isn’t reflected on paintings, because paintings disappear. They fall apart, turn to dust, burn or fade away. You see sculptures with arms chopped off, sphinxes with no noses. The Belvedere Torso is just a torso now. It’s that kind of stuff that inspires me most.

Academy: They are also weathered.

Holiber: And then you have this guy [looking at “Hero”], who is literally made of discarded manufacturing products, pallets and stuff. I want him to be a product of the environment and content that he’s this total mess. I don’t want to personify him. He’s a sculpture. I want the work to be what it is. It’s made of discarded wood and paint. I haven’t even painted his face yet. I can’t talk about the feeling I get from it. I think it’s different for somebody that’s just going to see it in the gallery and not having lived with it…a thousand times and put it back together. I want “Hero” to be simple. The others will be more elaborate.

Holiber: This better not suck. Often times for a body, I’ll start with a very simple geometric shape. Rectangle or square and then I’ll start to take it apart or I’ll cut half of it and start doing something that’s irregular. With this and the other ones, what I’m thinking when I am building this is don’t make anything too regular. I am trying to layer things and get these weird angles. I know I want the overall shape to be rectangular and weighty and very statuesque, but I want there to be a lot of dimension in the form. I don’t know if I think the same thing as you where I am trying to devote every decision to one feeling. I guess I am trying to build it in a way that’s interesting to me. Usually what’s interesting to me is the irregularity of things. A lot of it happens just as a byproduct of what ever shape the wood is that I pick up off the floor. My studio is a mess but it has to be like this because if it was all organized, I wouldn’t be able to find a little chip that has a cool shape. When this little thing popped out here [points to side of sculpture], I thought “Oh, that’s great, I’ll leave that.” And this shape, how it breaks like that, its stuff like that. When those things start happening, it gets really exciting for me.

Initially, my idea for the show was to create a little army – to fight the casts. Everyone would have weapons and all my sculptures were going to attack the casts. But instead, I thought if I build them a certain way and really focus on the installation of my sculptures with the casts together, the dialogue is still the same. The weapons don’t have to be there, it doesn’t have to be that literal. Besides the cast don’t have weapons any more because they are missing or have been broken. Originally I was going after a warrior kind of sculpture or statue. I guess I see these guys as warriors, confronting something. I don’t want to personify them but if I had to they would all recognize they are sculptures and everyone is looking at them, so they have a certain attitude where they are confronting the viewer through their pose or facial expression, they are very confrontational or aggressive. The way I build them is certainly aggressive in terms of technical narrative and emotional narrative, two big topics at school. I really try to mesh those two.

Holiber: Whenever I see something that looks too figurative, I have to take it apart. I guess if it’s too expected or it’s something that’s too familiar I don’t like it. Even this is the most simple kind of frontal stance, it still feels new to me. I remember at the beginning of school I was building this contraposto figure out of wood, just like he is. And something happened; it was too figurative. I did his knee really nice. I was so proud of the knee. It was all anatomically correct and it was beautiful, I was like this is great! Then I came in one morning, looked at it, and said, “No, this is not good.” I had to take it apart. It wasn’t working.

Academy: Why is that, do you think? It is mere, resistance?

Holiber: I don’t know if it had to do with just working against the school or what. Having been taught all these tools to accomplish something like that and then telling myself, “No, I don’t want to do that.” I am sure it was just me, not wanting to do the things I have been doing and learning for the past few years. It was also the artists I was looking at this past year. They are figurative artists, but not necessarily. They don’t make illusionistic type of work. It’s very crude.

Academy: Do you mind sharing whom?

Holiber: Three artists I looked at the most, this year: Huma Bhabha, Matthew Monahan, Thomas Houseago. I completely feel in love with their work. They definitely have a brutality that I connect with and I think their work, for me, is the most relevant socially and globally, the most relevant work out there today. I am not trying to make a political statement. Being alive today, everything you do is going to be political. I am just trying to put all my effort into these things and whatever comes out is just me.

Academy: I have heard you talk about the rules you’ve developed in your studio practice. Tell me more about them.

Holiber: I started creating rules for myself last year, when I was writing my thesis. My only rule then was not to work from photos, to take photography completely out of my studio practice. This past year, I started looking at Matthew Monahan. I read this amazing interview he has with Maurizio Cattelan. Monahan was talking about the rules he set for himself. He had this whole other list of rules. I realized I needed them, too. I adopted his rules, omitted some and added others, and came up with a new set of rules for myself that I’ve been following. I have started thinking about tweaking them some, but so far they’ll stick.

Some of the rules are:

2. No live models

3. No casting

4. No mold making

5. No fabricators

6. No electric saws

7. No “armatures”

8. No source material, which is new and still really hard for me. That’s one of the things I’ve tweaked, because I’ll have a little sketch and put it up on the wall and then start working on something in the vain of that sketch, but then I will end up taking it apart so it changes a lot from the original drawing. I think it’s ok to work from my own drawings. That’s the hardest part of making this work. Basically you’re in a hole with nothing but the materials. It’s really challenging. Houseago has a similar studio practice. In a few interviews I read, they talk about the chaos and the planning that goes into a work. They both, and I agree, think the work ends up being the best when it comes out of a process that isn’t pre-planned and it just happens. To do that is really challenging and frustrating. That’s why I like working like this so much because it is such a challenge. I literally have a pile of wood and some paint. Takes a lot of trial and error, most of my work is error.

Academy: Is it really error or is that how you work out the planning and sketching? If you’re not allowing yourself to do the planning and sketching, don’t you have to try it? Just do it and see what happens?

Holiber: Even if I have a sketch, I’ll make it and then it never looks the way it’s meant to. It’s never going to look like the sketch; it looks so good in the sketch. When you’re building it out of whatever material you’re using, there are constraints that the material has that you hadn’t taken into account. There are building problems you hadn’t taken into account. There are all these problems you have to solve in order to make it be what you want it to be. For me, I don’t really know what I want it to be and when I start coming across those problems, I have to decide if this is a problem I am going to try to solve or say “fuck it” and give up on the problem and just take it apart and start a new set of problems for myself. When you’re working from a photograph or that kind of source material that’s already solved for you there’s not much problem-solving going on and I am not growing artistically, as much as doing this work. The two types of work are totally different but I am constantly making problems for myself and learning from it, solving problems. Just copying something I don’t learn as much. The process of art making isn’t as enjoyable for me. I am not happy all the time. I am definitely frustrated and pissed-off, but the process is very important to me. If I don’t feel like I’m really creating omething there is no real point in doing it in the first place. In a crit with the faculty, Catherine [Catherine Howe, Full-time Faculty] asked me about the process of the work, and I said, “This is process-oriented work in the sense that the work comes out of a certain type process but it’s not a comment about the process. I’m not trying to make a statement on the process, it’s just my process.”

Academy: How was that received?

Holiber: She feels the same way about her work. It’s the way she works that determines what her paintings are going to look like. I guess now you could say that about everyone, but she has a certain freedom and looseness in the way she is very accepting of what happens on the canvas. I am a lot like that in my sculptures. There are accidents that happen in my work, I don’t want to say accidents because it makes it sound like it’s not on purpose. They are more like irregularities. The way a piece of wood breaks off or using a handsaw instead of a mechanical saw. There are all these things about my art making that will yield a specific outcome or look. For some angles I will be really controlled in my cut. For some I’ll use a hatchet. It’s not about me taking an axe to the wood; it’s about the work revealing itself. The irregularities are more pleasing to me, than a perfectly rendered smooth thing.

Academy: What was a favorite art show you saw in and around New York in the last few years? Two or three? Best art experience in New York 2013?

Holiber: Every time I go to The Met, I go through the Greek Galleryand then I go into the Africa Oceania and the Americas sectionsection. I could live there. That’s my favorite collection. There have been shows I liked and definitely pieces in shows I’ve liked but talking about emotion and feeling, when you walk through those galleries, there is no gallery in the city that rivals how those galleries make me feel. There’s an Inuit mask. It’s a bear mask, it has fur on the outside and it has abalone shell eyes and teeth and it’s just the most beautiful mask you’ve ever seen. It’s just so cool. I like that work so much, because it wasn’t just art to them it was so ingrained into their culture and ritual. I am pretty envious of that. Imagine if our culture was like that. What we were doing was like that.

Academy: It is. Think about it. The Catholic culture, the Christian culture. All the imagery of Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ.

Holiber: But it’s not as awe-inspiring as knowing this object was part of a ritual or ceremony. Even if I make something now that is totemic and like this, I’m not religious. We don’t have a culture that is devoted to the same thing. That’s the romantic idea; I am being super romantic because that’s the way I think about it.

Academy: I agree. The use of physical objects or visual imagery within the culture like that really changes the way we look at life and the way we look at art. The western culture is definitely intellectual, monetary culture, hierarchical. Other cultures from the start focused on nature. Western is more about abstraction and impurity.

I am curious about your own rituals in your practice. You have a process that is based on creation and destruction. Are there rituals that go along with that process?

Academy: Have you noticed that evolve?

Holiber: I have been painting with the same palette, give or take a few colors, since the beginning of my second year. I did a lot of palette experimentation my first year. I got really nerdy and into making my own palettes and mixing my own colors. I think it should be mandatory at school. I would say I paint in tints. I love mixing paint – secondary, tertiary, quaternary colors. I pay attention to my colors a lot. I feel like that’s the one thing I really have a strong hold on. The one thing I am good at. I have a good sense of color and use of color. That comes from messing around with different palettes. Painting I class, I’d have a new palette every week. Painting II, I would pre-mix a full palette before each assignment. I was one of the only kids doing that and I learned a lot from it. A lot of artists use a restricted palette – four colors or whatever. They’ll mix up colors as they go along. I mix everything on my palette and then apply it; I usually don’t mix on the work. I look at my palette more than I look at what I am working on. Everyone does it differently. I have to keep my palette extremely clean and organized.

Academy: Tell me about your Fellowship year. What was it like to have an extra year at the Academy? What were the benefits? Did anything unexpected happen?

Holiber: Having another year to concentrate on my work was the most valuable part of the Fellowship. Having that time, getting paid for it, and just getting to know everyone in the school more. I was close with a bunch of kids in my class, but when they left I was on my own again. It was cool, but it’s a difficult transition. You feel like you’re floating because you’re not a student anymore, but you haven’t left the school. You’re always coming to the school to work. The first month I didn’t talk to many people. I am sure there were a lot of people that were thinking “who the hell is that?” What class is he in? It takes me a while to get used to new situations. It took me awhile to feel like I was grounded in the Fellowship. The first few months, it’s a little weird because you’re in this new role. It was great because I started to get to know the staff and administration a lot more than when I was a student. That led to a lot of new friendships. I slowly got to know more students in the first and second year classes. By the end of the school year, I had a whole new group of friends and it was really great. Also, the feedback from other students and the faculty was available when I wanted it. When I wanted to be left alone and out of critiques, I could be. I wasn’t in class anymore getting weekly critiques. But when I needed to pull someone into my studio, I could do that too. It’s the best of both worlds. You’re working there in school all the time and you can be a student if you want to be, but at the same time you can check out and be a professional artist if you want to be. The resources are at your disposal.

Academy: It’s a boost. It’s a good kick in the ass, boost.

Holiber: I wish there was a little more structure. I don’t love getting critiqued but I feel like it’s necessary. I wish there was more structure with the fulltime faculty giving us critiques. We had a few throughout the year. Maybe two a semester would be good. It’s hard. The school is so small. The faculty has so much responsibility. It was easy for me to be on my own for a while, but maybe I needed that. The only other difficult thing I can think of is you’re in school for another year. You’re in school, but you’re not. It’s not the real world yet. Everyone I graduated with has jobs now, some are working for artists and now I am going through that. I am a year behind. It’s not a big deal. I miss some of those guys. I haven’t seen them in a while.

Academy: It’s a good place to be, in school.

Holiber: Yeah. I love some of the people from my class. It was weird to be on my own and get thrown into it. But it was good. I can’t complain that’s for sure.

Academy: Was there a good “jiving” going on between you, Jon, and Aleah during your Fellowship year?

Holiber: I think so. Aleah and I collaborated a little bit and that was a lot of fun. Aleah and I went to Leipzig together, so we’ve always been talking to each other about our work and helping each other through stuff. Jon I shared a studio with my first year, so we’ve always been talking as well. Our work, the three of us, is totally, totally different. It couldn’t have been further from each other. As far as being a support system, the both of them, I think all three of us were really supportive. If we ever had a question or wanted to throw some ideas back and forth, we could just go up and pop into the studio.

Holiber: In a weird way, I think my work acts as an intermediary between Jon and Aleah’s work. Especially because Aleah is doing more landscape stuff now, really getting into the environment. Jon is all about environment. My work is materials from our physical environment plus the figurative element. I think it’s going to be great. Jon is doing those constructions too where he has raw wood exposed with different materials. I think it’s going to work really well together. Our work is very different but it has a similarity that will mesh well when it’s in a common space. Usually every fellow has a wall. I think we’re going to mix it up and put everything everywhere.

Academy: I can’t wait to see it.

Holiber: Me either. I have to finish this.

Academy: What do you have planned after the Fellows Show?

Holiber: Going to take a little break. My plan is to find a new studio and keep working. I work really well under pressure, so having the show and the deadline has been good. But I am also looking forward to taking more time to experiment with different materials and forms. I guess playing around a bit more. I was very pressed for time this summer and didn’t have three or four days to sit there and look at something to decide if I liked it or not. If I didn’t like it, I had to take it apart and make something else right away. I am looking forward to having more time. I like the pressure. It pushes me a little differently than if it’s just me working. I’m also really looking forward to this new job I got. I’m going to be working in a metal fabrication studio. We’re fabricating a sculpture for an artist. Welding is something I’ve wanted to do for a while. I’ve been told when you can weld you can make anything you want. That’s going to be pretty cool. When I went for the interview I had to do a welding test. It’s the coolest thing I’ve ever done. I was jumping out of my seat. You basically have a lightning rod in your hand. It’s incredible.

Academy: Sounds like great things to look forward to.

###

Giverny, Giverny, Giverny…you can certainly hold your own: Giverny 2013 Residency, Part 1

August 10th, I arrived in Paris to meet with the Chilean women of the group, Alonsa and Daniela. We succumbed to the forces of the infamous Sennelier Store, almost in tears as we left, not because we were sad, but because we were persuaded by our worse judgment to buy way more supplies than necessary.

Then, as the weekend was over, we boarded a train to Vernon, a neighboring town just outside of Giverny. As we stepped off the train, we were surprised to find that the other Academy students had been riding along in the same train. This was the first inclining as to just how small Giverny was.

Giverny allowed us to create art and art alone. It gave us the freedom to do what we love without the worry and burden of everyday life. Its culture, its beauty, and its charm have changed the way we see. I have also left with friendships that are much stronger than when we first stepped off that train.

.jpg)