ICONOMANCY

![]()

- Ali Banisadr (MFA 2007)

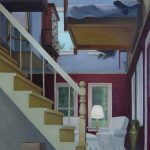

- Amy Bennett (MFA 2002)

- Amy Bennett (MFA 2002)

- Will Cotton (Senior Critic, Tribeca Ball Honoree 2017)

- Natalie Frank (2002)

- Tat Ito (MFA 2008)

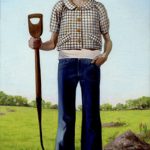

- Will Kurtz (MFA 2009, Fellow 2010)

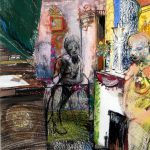

- Bryan LeBoeuf (MFA 2000)

- Francesco Longenecker (2007)

- Matthew Miller (MFA 2008, Fellow 2009)

- Matthew Miller (MFA 2008, Fellow 2009)

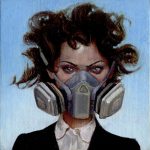

- Alyssa Monks (MFA 2001)

- Peter Simon Mühlhäußer (MFA 2009)

- Peter Simon Mühlhäußer (MFA 2009)

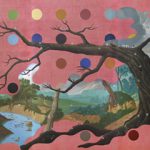

- Jean – Pierre Roy (MFA 2002)

- Melanie Vote (MFA 1998)

- Melanie Vote (MFA 1998)

- Melanie Vote (MFA 1998)

- Matthew Woodward (MFA 2007)

- Matthew Woodward (MFA 2007)

-

Matthew Woodward

MFA 2007

- Matthew Woodward (MFA 2007)

EXPERIENCE at Today Art Museum. Beijing, China

Yesterday we visited the Today Art Museum. There were two solo shows by female sculptors Xian Jing and Li Wei. Xian Jing’s show “Will things ever get better?” began with a huge 100 foot tall space presenting contorted knots of acrobats. They were composed on 30 foot tall welded pedestals, stacked on top of each other, or quietly poised and meditating before taking action. An ambitious feat of sculpture, these resin sculptures painted meticulously with acrylic were performing for us, smiling, waiting tensely for our applause.

Yesterday we visited the Today Art Museum. There were two solo shows by female sculptors Xian Jing and Li Wei. Xian Jing’s show “Will things ever get better?” began with a huge 100 foot tall space presenting contorted knots of acrobats. They were composed on 30 foot tall welded pedestals, stacked on top of each other, or quietly poised and meditating before taking action. An ambitious feat of sculpture, these resin sculptures painted meticulously with acrylic were performing for us, smiling, waiting tensely for our applause.

This gallery was divided by a deep red velvet curtain which behind it held more fantastical works. Dramatically lit, life size painted animals like the “immortal one”, a dopey elephant, big eyed horse, sheep, and a group of seals. Installed in a smaller space, you were at level with these animals, intimate and up close to the pathetic and hopelessness of their pose. There was a distance in their hollow gaze, unaffected by your presence. It simulated the detachment and exhaustion of animals at the zoo.

In another warehouse space at Today Art Museum was Li Wei’s Solo show “Hero”. Unaware about any of this artist’s ovure, I walked into a long hall that led into a large open space. All I could see ahead of me were two kissing fire extinguishers and I thought to myself, “Please don’t let that be the work of art.” As I turned the corner there were 20 sculptures of Chinese girls and boys in dancing costumes, big glass eyes staring eagerly, nervously at me. A huge theater spotlight beamed on their stage frightened bodies. I felt bad for these little ones, knock-kneed, pleading internally not to be judged and awkward in their costumes that can’t hide the anxiety of their budding adolescence. A gaggle of young persons walked in, giggled and pointed at the sculptures. Perfect.

Walking out, I was led into the spaces upstairs. First there was a flock of flared peacocks flirting with each other on astro-turf. But to my right was room with a beeping noise that persuaded my attention. I entered the glass door to find four beds with near death figures in a tangle of medical tubes and sensors on their bodies. It smells sick, stale, and sterile like a hospital. Blaring, insensitive florescent light floods the 15’x10′ small space, leaving me to confront the bodies before me. Fluids are bubbling through tubes and regulators while I try to distinguish the life left in these forms. Flesh in complete repose, their naked bodies sprawled open in a tangle of bed linen don’t reveal their sex until you follow the lines of their tubes and find penetrating catheters. I am repulsed and drawn in simultaneously. As I aim to photograph I stall; feeling at my core wrong about documenting these barely alive figures. Standing bedside between two of the figures my head darts back and forth between their glazed eye contact. Tubes billow out of their mouth and dismembered bodies; I am stunned between their utterly silent stare. A man comes in and begins pulling cords out of the machines, and the beeping of their life force goes quiet, their bubbling fluids cease. I look at him in shock, “What are you doing! Why are you pulling the plug!?” He smiles back at me; responding, “Hel-lo!” I notice another gallery attendant ready to lead me out because it is closing time.

Walking out, I was led into the spaces upstairs. First there was a flock of flared peacocks flirting with each other on astro-turf. But to my right was room with a beeping noise that persuaded my attention. I entered the glass door to find four beds with near death figures in a tangle of medical tubes and sensors on their bodies. It smells sick, stale, and sterile like a hospital. Blaring, insensitive florescent light floods the 15’x10′ small space, leaving me to confront the bodies before me. Fluids are bubbling through tubes and regulators while I try to distinguish the life left in these forms. Flesh in complete repose, their naked bodies sprawled open in a tangle of bed linen don’t reveal their sex until you follow the lines of their tubes and find penetrating catheters. I am repulsed and drawn in simultaneously. As I aim to photograph I stall; feeling at my core wrong about documenting these barely alive figures. Standing bedside between two of the figures my head darts back and forth between their glazed eye contact. Tubes billow out of their mouth and dismembered bodies; I am stunned between their utterly silent stare. A man comes in and begins pulling cords out of the machines, and the beeping of their life force goes quiet, their bubbling fluids cease. I look at him in shock, “What are you doing! Why are you pulling the plug!?” He smiles back at me; responding, “Hel-lo!” I notice another gallery attendant ready to lead me out because it is closing time.

Adrenaline pumping, I exit the gallery, beaming from the empathy I felt for the figures and the complete submersion I experienced. The powerful simulation in both rooms; an endearing anxiety with the costumed adolescences, and the transfixion on the bodies with their wavering mortality preserved by pumps and tubes.

See more pictures from the show below:

Introduction to Shanghai/Beijing Residency

|

| Left to right: Wang Yi, MFA 2010, Mitchell Martinez, Class of 2012, Samuel Evensen, MFA 2008, Cori Beardsley, MFA 2011, Kiley Ames Klein, MFA 2011 Friend, Cao Yi, MFA 2011 |

NiHao Academy community! I wanted to introduce the CAFA, Shanghai University Residency program that Kiley Ames Klein, Samuel Evensen, Mitchell Martinez, and myself; Cori Beardsley have been on since August 20th. Wang Yi (alum Shanghai University-2008,NYAA 2010) and Cao Yi (Alumni of CAFA-2009, NYAA-2011) have been our generous, energetic tour guides, translators, and dear friends-welcoming us so warmly into China and explaining the culture, art and history along the way.

We started out in Shanghai, visiting cultural sights like Old and New City, museums, and important galleries. Staying at the University Hotel at Shanghai University, We met 15 students from Shanghai University and other Universities in China (graduate and undergraduate). We worked from the model, and on our own projects in the studio with them for 10 days. We also traveled and worked Plen air for two days to Xi Tang, a beautiful ancient water city. Back at the studio, Samuel Evenson led a great anatomy class one morning and we exchanged in discussions about our contemporary art worlds, working representationally, and what we strove for as artists. Wong Yi’s took us to his studio and we were thrilled about his new work. He also took us to local markets and antique shops- insight about the history of China that gets submerged in the sea of modernization.The generosity and hospitality we received in our introduction to China was overwhelming, our big wide eyes were busy taking in all the new sights, people and culture.

And off we were on a FAST 5 hour train ride to Beijing. We are staying in an apartment that Cao Yi found for us that is a half a mile from school, and we have a terrific 1,000 sq. ft studio with a skylight in the Graduate Oil Painting Building. After we stopped jumping up and down in the studio we quickly got to work. Art supplies are very cheap and accessible, the spaces are BIG and the art is BIG. So our ambitions went soaring. Ren Rui and Janet Fong from the Public Education and Development Program at the Museum of CAFA are arranging a show for us of the work completed on this Residency in the Museum while the Biennial: Super Organism at the Museum is up. To be continued…

A Teachable Moment

________________________________________________________________________

– Holly Ann Sailors

, MFA 2012

_________________________________________________________________________

Examples of artwork dealing with controversial themes (some w/links):

|

| Chris Ofilli: “The Holy Virgin Mary” (link) 1996 |

|

| Kara Walker |

|

| unknown racist illustration |

|

| Peter Saul: “OJ”1996 |

|

| Glenn Ligon: “Benefit” 2007 |

|

| Lisa Yiskavage: “Pie Face” |

|

||

Gustave Courbet: “Dreamers”

|

|

| Carroll Dunham: “(Hers) Night and Day” |

|

| Gustave Courbet: “Origin of the World” 1866 |

|

Robert Mapplethorpe: “Fisting” 1978 Carolee Schneemann: “Interior Scroll” |

Not to Miss

Welcome back Everyone! School is in session and so is the fall season.

Tonight don’t miss NYAA Senior Critic Vincent Desiderio’s opening at Marlborough in Chelsea. This haunting new series of paintings explores the subtle, underlying context of the human experience through exquisite brushwork and a profound technical narrative.

Tonight don’t miss NYAA Senior Critic Vincent Desiderio’s opening at Marlborough in Chelsea. This haunting new series of paintings explores the subtle, underlying context of the human experience through exquisite brushwork and a profound technical narrative.

Also opening in Chelsea, James Cohan is proud to present DANDAN, a solo exhibition by Japanese artist Tabaimo, who represented Japan in this year’s Venice Biennale. Elaborate stage sets were built in the gallery to showcase her incredible hand drawn animations.

Uptown at Gagosian, go see NYAA Senior Critic and last year’s Commencement speaker Jenny Saville’s new show of life-size drawings and paintings exploring the renaissance theme of Madonna and child. Known for her lush, fleshy figures, this is Saville’s first show in NY since 2003.

Afterwards head to the Lower East Side to Kleio Projects for a show curated by NYAA Alum Benjamin Martins and inspired by fellow alum Maud Taber-Thomas. Self Portrait As Monster Truck will feature a number talented Academy artists, past and present, with their interpretations of the title theme.

As for shows that have already opened don’t miss the following;

Alex Katz at Gavin Brown. This is Katz’s first show after leaving Pace Wildenstein for Gavin Brown. The show juxtaposes Katz’s classic somber portraits with minimalist fields of flowers.

Do So Huh at Lehmann Maupin. Home Within Home is an array of installations and sculptural objects that all explore themes of cultural displacement. The centerpiece of the show is a scaled up apartment building ‘dollhouse’ where Suh lived in Rhode Island impaled with a model of his Korean home.

Nick Cave at Jack Shainman. A new series of Cave’s meticulously covered figures in various vignettes exploring individualism, unity, fornication, memory, and the inheritance of personal identity.

Nicole Etienne at Sloan Fine Art. The NYAA Alum’s show aptly titled A Movable Feast, features Etienne’s glitter-filled, overexposed, multimedia interiors superimposed with lushly painted figures, flora, and fauna.

Pitch at RH Gallery in TriBeCa featuring South African artist Paul Edmonds. In this series of ethereal, abstract drawings Edmunds seeks to find a visual correspondence to music specifically in relation to pitch, tone, timbre and stereo.

The accompanying group show Melodymania, referencing a tune you can’t get out of your head, includes NYAA Alum Panni Malekzadeh, Mickaline Thomas, Mathew Barney, Slater Bradley, and Bruce Nauman among others.

And last but not least, Stefanie Gutheil at Mike Weiss. Gutheil’s paintings are vivid, large scale, maximalist combinations of characters, shapes, and patterns.

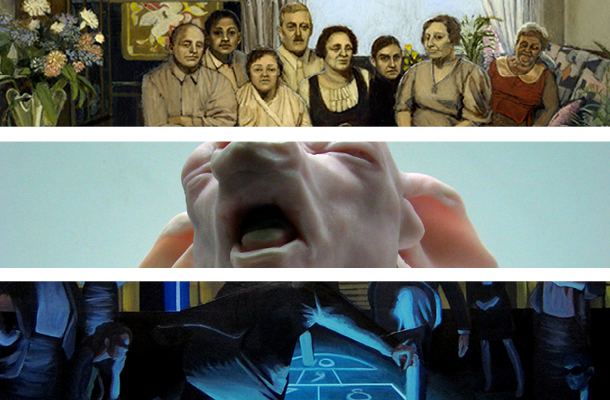

Fellows Exhibition 2011

Artwork (details) top to bottom: Maya Brodsky (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011), John O’Reilly (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011), Austin Park (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- Maya Brodsky (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- Maya Brodsky (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- Maya Brodsky (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- Maya Brodsky (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- Maya Brodsky (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- Maya Brodsky (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- Maya Brodsky (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- Maya Brodsky (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- Maya Brodsky (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- Maya Brodsky (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- John O’Reilly (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- John O’Reilly (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- John O’Reilly (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- John O’Reilly (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- John O’Reilly (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- John O’Reilly (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- John O’Reilly (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- Austin Park (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- Austin Park (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- Austin Park (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- Austin Park (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- Austin Park (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- Austin Park (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

- Austin Park (MFA 2010, Fellow 2011)

Quentin McCaffrey in Carrara, 3

by Quentin McCaffrey, MFA 2011

After selecting a stone, a warm and pale white marble taking its name, “Statuario”, from its historical use, I was given a place to work and all the tools and advice necessary to extract form from stone. Seeing that I was basically just scaling up an existing work and transferring it into a different material, the “formula†for achieving the sculpture was actually rather logical; however beginning was probably the most difficult part.

In Carrara, small chunks of marble like the one I was using are often dumpster worthy scraps. Still, I felt very precious at first about the material, and I was overly sensitive to its inability to forgive. I began working very cautiously, taking measurements, slowly carving away some stone, measuring, sawing off an unwanted corner, measuring again, etc. The bulky square of the original stone was diligent and did not want to submit to the saws, chisels and hammers.

This went on for almost the whole first week. The days were long and my inexperience and fears caused me to work slowly, as if the weight of the stone literally remained upon me like a burden. I became Sisyphus or Bunyan’s Christian.

The evenings however, were spent as the Creator intended. Pizza, frutti di mare, pasta and wine were shared and enjoyed over stimulating conversation. We left our (or maybe just my) stiff, anglo-american rigidity behind and finally understood rest.

Once every few days, for an afternoon or the whole day if necessary, the relative closeness of Florence or Siena would beckon us to their treasures and we would escape the dust, trading it for Cathedrals and museums. Florence, swollen with sculptural ecstasy, revealed the potentials of stone, humbling all who bear witness. Michelangelo left us only grace and power, the weight relieved, even in his slaves still bound to the rock. The glory of the work overwhelms you at first with its size, subtlety and charisma. Eventually, your mind regains itself, the facts pour in and you are stupefied again. Without power tools, and restricted to daylight and fires, these heroes of old orchestrated the marble and it sang their symphonies as they squinted through the settling dust.

At some undefined moment, back in the studio, the stone eventually softened and its weight slipped away. The form I knew began to peek through and assure me that it was hiding in there, and I needed only to carve away the superfluous material and the sculpture would reveal itself. The corner turned, the curve rose exponentially, and it felt as if Sisyphus defied the gods and the stone tumbled over the pinnacle. It was at this point that carving became a joy and the lovely roundness of the forms started to teeter between stone and flesh.

At some undefined moment, back in the studio, the stone eventually softened and its weight slipped away. The form I knew began to peek through and assure me that it was hiding in there, and I needed only to carve away the superfluous material and the sculpture would reveal itself. The corner turned, the curve rose exponentially, and it felt as if Sisyphus defied the gods and the stone tumbled over the pinnacle. It was at this point that carving became a joy and the lovely roundness of the forms started to teeter between stone and flesh.

It was the days following this moment that became the filet of the residency. Having a better grip on the direction of the work allowed me to see what else was going on around me. Watching and listening to the artisans in the studio (as I butchered their festive tongue) and the parallel experiences of my fellow students proved invaluable and became a classroom of its own. Steve’s consistent encouragement and balance of instruction with allowance for personal discovery permitted confidence in the work while maintaining room for a sense of individual growth and exploration.

It was the days following this moment that became the filet of the residency. Having a better grip on the direction of the work allowed me to see what else was going on around me. Watching and listening to the artisans in the studio (as I butchered their festive tongue) and the parallel experiences of my fellow students proved invaluable and became a classroom of its own. Steve’s consistent encouragement and balance of instruction with allowance for personal discovery permitted confidence in the work while maintaining room for a sense of individual growth and exploration.

Quickly the days escaped and the time to leave approached. Shipping arrangements and final trips for the acquisition of coveted Italian tools were made as the hours slid by and were gulped down with the house wine at final meals together. Goodbyes were said, contacts exchanged, Facebook requests confirmed and we parted ways, some staying to work, others sightseeing; me, alone moving north-east to the Biennale in Venice. The trip, in its totality, was exquisite, as if composed by a master of temporal engineering. I would be hard pressed to find a more perfect follow-up to a work-filled semester than the balance of rest, exploration, work and study that was my June in Italy.

ALUMNI SPOTLIGHT: Doris Buehler

What are you currently working on?

I was been preparing for a Single Show at the Gallery Bachlechner, in Zürich, June 18th -31st July 2011. I showed a collection of sculptures, paintings, mixed media and some animatronic pieces around the “belly button”. I have also created a series of wax pieces called Burning Issues that highlight some of the concerns we as human beings have regarding our political and social environment.

I am moving away from the traditional forms that I have previously used and exploring a far more abstract state which I enjoy immensely. This allows me greater freedom in my communication; addressing the issues of today in a way that is more congruent with my feelings. The belly buttons, and the wax pieces, have allowed me to show a slightly more frivolous side, playful and exciting. However, the “belly button” is built around more serious messages. The “belly button†or the Umbilicus Urbis*

What was your most recent big thing?

I currently have a splendid show in a beautiful Park in the South of Switzerland. I also participated at a major event in Switzerland in 2009 where I showed a couple of life-size pieces called “in between” and “Gaia”. I have also shown works in Germany, Israel and the USA.

|

| Doris Buehler, in between, 2009, Lifesize, Acrystal Prima, Size of Glass 1m x 2m high |

What do you find challenging about your work?

To set a goal of where I want to be with my art in 10 years from now. Since my art encompasses so many different materials and styles it is hard to decide with which I should precede. In the studio I find that the biggest challenges are to find the right materials and reliable suppliers, organising shipping, and organising other people to deliver on time and against promises! Finding time to do my PR, maintain my website, design invitations and plan events is also a challenge, there never seems enough hours in the day. I must get to do that project management workshop!

What do you find rewarding?

The paycheque is nice but much more rewarding is the joy to create, to develop an idea with the right material to attain the utmost expression of what is on my mind. Also I find it rewarding to catch people’s interest and make them curious.

What’s on the horizon for you?

Currently I have two private commissions in the pipeline that will keep me busy until the fall. I have been asked to show a big piece in New Orleans. I am however most excited to put aside some spare time to create a new body of work, a lot of which has been in the drawer for a while, and show it towards the end of the year.

Doris Buehler

http://www.dorisbuehler.li

Carrara, 2

I decided that it would be best to arrive in Italy prepared to start carving immediately. I have been developing a series of simple beeswax heads that hang off the wall. It seemed fitting to make a plaster cast of one of these pieces that I had already become very familiar with, and then attempt to recreate it in stone. I hypothesized that learning the process of transferring the design in three dimensions would simultaneously allow me to see how a different material might shift the content of the work. It also seemed plain to me that the design would not carry perfectly into the new material but would become its own work distinct from the preliminary piece.

Although I much of my recent work has utilized wax, I really don’t see myself as “the wax guy†as much as a materially sensitive artist. I would love to make shows based on the medium of the work. A show in bronze, clay, fabric, glass, resin, stone, wax, wood, etc. I really believe that the material is part of the language of the work, particularly in three dimensions, even though it needs to subject itself to the content and form and not become a novelty or a crutch. This is proved clearly by the Rodin sculptures that are glorious in cast bronze but fail when attempted in marble. The artist’s hand is removed; the work is not the same or even good. The sculpture is somewhere else, maybe it stayed in the 20 minute sketch, but it never swelled into life when it met the firm solidity of stone. This was a situation I wanted to avoid. Doing the work myself, opposed to hiring an artisan to do all of it was a step in the right direction, but did not ensure success.

After arriving in Italy and enjoying a week gorging on Caravaggio, Michelangelo, Bernini and other sweet and savory treats in Rome, I rode the train north and slightly west along the intoxicating coast to Carrara-Avenza where Steve Shaheen, one of my sponsors and the sculptor who would be teaching me about stone, graciously picked me up, despite being 3 hours late (perhaps by Italian standards this was par for the course). From the first moment it was clear that Carrara was the optimal location for carving stone. The mountains, peering down on the towns cradled between their foothills and the turquoise sea, are full of marble. The quarries clamor up the mountainsides with zig-zag access roads and even burrow into the depths of the mountains, excavating the rocks in cool darkness. Along the coast area, cranes and hangar-like buildings appoint the numerous workshops where artists and artisans, devoted to the creamy marble and the forms that may emerge from it, toil in powdery dust.

After arriving in Italy and enjoying a week gorging on Caravaggio, Michelangelo, Bernini and other sweet and savory treats in Rome, I rode the train north and slightly west along the intoxicating coast to Carrara-Avenza where Steve Shaheen, one of my sponsors and the sculptor who would be teaching me about stone, graciously picked me up, despite being 3 hours late (perhaps by Italian standards this was par for the course). From the first moment it was clear that Carrara was the optimal location for carving stone. The mountains, peering down on the towns cradled between their foothills and the turquoise sea, are full of marble. The quarries clamor up the mountainsides with zig-zag access roads and even burrow into the depths of the mountains, excavating the rocks in cool darkness. Along the coast area, cranes and hangar-like buildings appoint the numerous workshops where artists and artisans, devoted to the creamy marble and the forms that may emerge from it, toil in powdery dust.

I was to work in one such bottega for the next two weeks. Studio Corsanini, complete with its patriarch Luigi (freely doling out his acquired wisdom both in stone work and general life, and doubling as head-chef who prepared glorious lunches for all), Zen-master/Sculptor/Age-defier Itto Kuetani, and a colorful selection of hard working house artisans, was a brilliant place to see a wide variety of working methods and ideas in action in the realm of marble carving.

ALUMNI SPOTLIGHT: Joan Benefiel & Jeremy Leichman

|

| St. Ignatius Commission |

What are you currently working on?

Jeremy Leichman and I met at the Academy and are both sculptors. We have our own sculpture studio business together, Figuration LLC. We’re currently working on finishing up the bronze castings of a pair of our life-size bronze sculptures of St. Ignatius to be installed in October, commissioned by Fairfield University.

What was your most recent big thing?

We have a beautiful installation – the Fashion District Pilings Project – still on view through August 29th on Broadway between 36th-41st Streets on the pedestrian plazas of the NYC Fashion District. Our sculptures were even in The Wall Street Journal’s Photos of the Week: July 11-15 (photo 9/20)!

What do you find challenging about your work?

It seems like there is no clear path to making a career out of this sculpture thing. You have to make it part of your practice to always be looking for the next job if you really want to make a living out of doing what you love and not be distracted by other things. And we’ve decided that this is the most important thing and the only way to truly do it full time, all the time.

What’s on the horizon for you?

|

| Read an interview from Flavorpill with Joan Benefiel about the Hudson River Pilings Project |