When is a failure not a failure?

Dear friends,

They say that if you are not failing you are not trying hard enough, and also that failing is good because then you can learn from your mistakes. But art is a subjective field – how do you tell if your work of art is a failure or not? My dealer Mary Boone considers every painting in an artist’s oeuvre to be an essential, even if it seems to come out of left field. Therefore, works of art that “fail†in fact are often stepping-stones to some of an artist’s best works.

That may be true, but one of my unconventional techniques to “clear my head†and develop high quality new work has been – quite simply – to throw things away. Years ago, I was living in San Francisco and was working on a painting that I felt wasn’t coalescing. Though I’d spent months on it, I ended up leaving it on a sidewalk. Disposing of it completely left room for me to make my following painting, Shore Leave (2001) which is in the collection of the Whitney Museum. I also threw away another painting I wasn’t happy with in 2000, when I was living in Chelsea. I handed this painting to the porter of my apartment building, and he sad “nice painting†before flinging it in the dumpster. I was sad the painting failed, so I replaced it by painting Iowa Class (2003), in which a sailor stitches her own face after being wounded in the line of duty or perhaps a brawl (a painting I’m really proud of).

Perhaps you don’t need to go to such extreme measures in clearing away the cobwebs. But sometimes bucking the conventional wisdom will allow you to open yourself up to possibility.

|

| Iowa Class, 14 x 22 inches, oil/linen, 2003, Mary Boone Gallery |

|

| Shore Leave, 12 x 15.7 inches, oil on panel, 2001 |

Yours very truly,

Hilary Harkness

Miami Basel

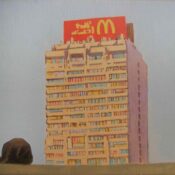

Think what you may about the commercialization and commodification of art but it is unavoidable. Art fairs, though the pinnacle of the trade show business model, are a critical part of maintaining a contemporary dialogue and can be an integral part of exposure for many artists. If anything, art fairs are a reassuring reminder about how vast the art world really is. Though they occur globally and at multiple times during the year, none offers the spectacle and debauchery of Miami in early December.

Basel began in Switzerland in the 1970’s and started in Miami in 2002. Though it is the moniker for the high brow show an the Miami Beach Convention Center it has come to be an umbrella term to include the many satellite fairs surrounding it. There is an endless amount of art, people watching,and parties. South Beach is overrun by collectors, advisers, press, artists all looking to have a good time. This year was seemingly an art buying frenzy; perhaps to encourage buyers but spirits generally appeared high. One dealer I spoke with said she was astonished by the amount of work sold with in the first hour of opening. Hopefully this is a sign of years to come. Some trends I noticed were explosions, artists using holograms, a great deal of figurative work and Massimo Vitali. His hyper real beach photographs were everywhere. So was Terrence Koh, the person.

Below I have complied some of the work I was most drawn to from the various fairs and my general impressions:

B A S E L

an intricate thread painting by Emil Lucas;

and a very Americana painting called the Bowery Girls (detail) by Kim Dingle.

N A D A ( New Art Dealers Association)

NADA is one of the younger hipper fairs and takes place at the Deaville Beach Resort. You can constantly look at the ocean while checking out the art. It showcases many of NYC Lower East Side galleries. Mostly works on paper though the booths are a bit smaller so its fitting.

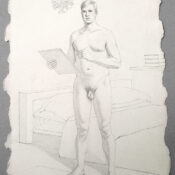

The first booth I encountered featured works by Nick van Woert who shows with Yvon Lambert. Modern Painters believes he is an artist to watch. I did get the issue free at the fair, but he has been popping up in a few collections. Though the show featured several gestural works on paper, van Woert is known for his classical casts covered in goo.

Then I ran into Eve and Adele, two of my favorite Basel fixtures. This German artist duo is the subject of many a work of art; hundreds of people photograph them and then Eve and Adele make drawings from the photos.

Leo Koenig had a small but beautiful painting of a woman lying and reading in her bikini titled Rooftop, 2010 by Ridley Howard.

At Paul Petro (Toronto), I was captivated by the work of Stephen Andrews. The Canadian artist’s work imitates various modes of mechanical reproduction such as the CMYK dot matrix in print, film or television technologies. The pictures are painstakingly rendered by hand in an attempt to represent both the message and the means by which it is delivered.

P U L S E

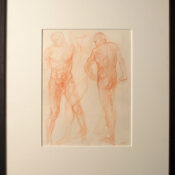

Pulse features younger galleries that are a bit more established. I saw a great deal of figurative work there including the work of NYAA alum Amy Bennett who was showing with Richard Heller. There was a red dot.

Freight and Volume was showing this slick oil painting by the multi talented Richard Butler, who also founded the Psychedelic Furs.

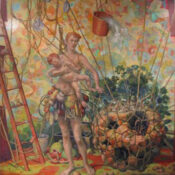

This amazing Brueghel-like painting (detail below) by Erik Thor Sandberg at Conner Contemporary (Fl);

This drawing by Michael Waugh (detail below) of a wolf made out of writing, also very much a trend.

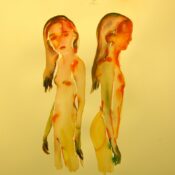

A watercolor by NYAA visiting critic and friend Kim McCarty at M+B;

And another beautiful porcelain figurative sculptures by Caro Suerkemper;

There was also this little beauty by Gretchen Ryan at Blythe Projects (LA). Painting child pageant queens was something I had always considered. There is so much art at the fairs its hard not to recognize yourself in some of the work. Seeing someone else carry out an idea you share has one of two outcomes; you either try to do it your way, or realize you don’t need to anymore.

S C O P E / A r t A S I A

Scope was showing with artAsia again this year in the Wynwood district. I ran into NYAA faculty member Jean Pierre Roy at the Rare Gallery booth showing some of his recent paintings.

| JP (right) in front of his paitnting, The Broken Sleeper. See more at Rare Gallery. |

Christopher Henry gallery had an amazing room installation by knit bandit OLEK whose knitted pieces you may have seen around NYC. The closest to school is the bike on Greene street between Canal and Grand.

There was this take on Arcimboldo and Delacroix by Ju DuoQi called “Liberty Leading the Vegetables”

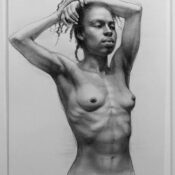

A sensitive set of drawings by Corrine von Lebusa at Silas Marder Gallery (NY);

Some beautiful figurative work by Yigal Ozeri;

This fanciful flight painting by Jose Garcia Cordero.

Scope also had a section of walls this year featuring murals and design including wallpaper by Brooklyn company ESKAYEL, designed by artist Shanan Campanaro.

Z O O M

Zoom is the Middle Eastern Art Fair. The Middle East is such a dynamic part of the art world right now; on one hand you have a burgeoning art scene ie. the projected Louvre complex in Abu Dhabi, on the other many artists and writers imprisoned for their beliefs. Its hard to imagine what its like to be working under a restrictive political regime or in exhile from it. What questions they must face; to make work as protest, whether to avoid cliches or reinforce them.

At Galerie El Marsa in Tunisia I was taken with these paintings by Hicham Benohoud;

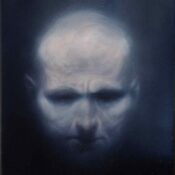

Robischon Gallery (CO) had these haunting photos by Halim Alkarim;

Another painting in writing, (artist unknown);

Other Openings and Activities

Outside of the fairs there was a range of openings and exhibits including a small island show sponsored by LAND (Los Angelas Nomadic Division) and Opera gallery sponsored a vacant condo building of Mr. Brainwash’s work, the graffiti artist whom the Banksy film ‘Exit the Gift Shop’ is about. The beachfront ‘Exhale Pavilion’, funded by Creative Time, was done by architect and industrial designers Phu Hoang and Rachely Rotem. It was constructed of seven miles of reflective and phosphorescent ropes. Designed to interact with its environment, the ropes move with the breeze and even glow depending on the wind speed.

Outside of the fairs there was a range of openings and exhibits including a small island show sponsored by LAND (Los Angelas Nomadic Division) and Opera gallery sponsored a vacant condo building of Mr. Brainwash’s work, the graffiti artist whom the Banksy film ‘Exit the Gift Shop’ is about. The beachfront ‘Exhale Pavilion’, funded by Creative Time, was done by architect and industrial designers Phu Hoang and Rachely Rotem. It was constructed of seven miles of reflective and phosphorescent ropes. Designed to interact with its environment, the ropes move with the breeze and even glow depending on the wind speed.

And then there are the hotels, palatial monuments to nightly activity, most of it poolside. You can see the whole cast of characters; such as the art consultant from the Mona Lisa Curse, calling out to Larry Gagosian in the lounge of the W where Steve Martin speaking about his new book on art. Its pretty over the top. The best party, as usual, was thrown by Jeffrey Deitch. He had LCD Soundsystem play a show at the Raleigh and danced the whole time. The man never ceases to amaze me.

Finally, there is the beach; the perfect place to spend your last day in Miami.

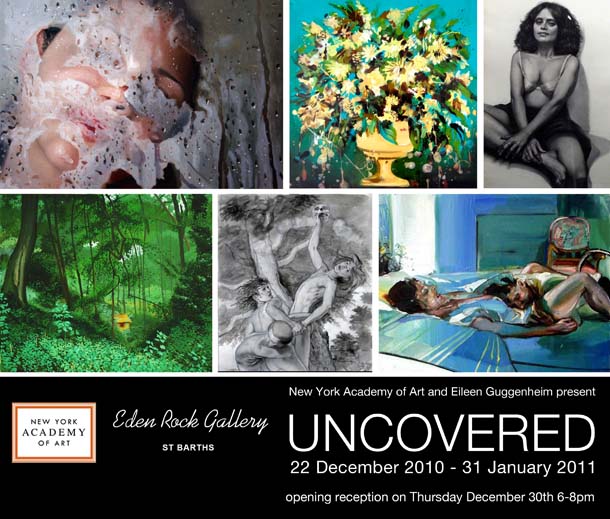

Uncovered

- Steven Assael

- Margaret Bowland

- John Bowman

- Lynda Churilla

- Harvey Citron

- Rosson Crow

- Ken Currie

- Christian Fagerlund (MFA 2004)

- Robert Feintuch

- Natalie Frank

- Julie Heffernan

- Catherine Howe

- David Humphrey

- John Jacobsmeyer

- Kurt Kauper

- Dik F. Liu

- Kim McCarty

- Alyssa Monks (MFA 2001)

- Jean-Pierre Roy (MFA 2002)

- Wade Schuman

- Robert Taplin

- Barbara Vaughn

- Nicola Verlato

- Saya Woolfalk

The “Post-Crit Elixer”

By Catherine Howe, instructor

As one who has given and received countless critiques in the (too many to mention) years since I was in grad school myself, I would like to share with you some tips for making the most of your Thesis Project critiques.

- The most important thing I can tell you is keep is talking! Do not clam-up or shut-down/shop-for-the-holidays just yet… Talk with your fellow students. Share ideas while the experience is fresh.

- Write down the main ideas and comments that came from your critique and any questions you have about them.

So, what do I do with those ideas now?

Separate the ideas into the “macro” and the “micro”- in other words, identify the main points versus the trivial. This can be done with others if it is more fun.

1) Look through them and make a list of any structural or BIG issue comments that resonate with you but which will need to be addressed before moving on.

2) These macro issues will require some extended thought in the form of dreaming, scheming, what-if? explorations, and conversations with yourself. You may need to pull down some existing idols or get a New Year’s makeover.

3) Re-visioning. Give yourself time but keep making things while you do it. The works you do while you’re re-visioning can be “unimportant,” and never need to see the light of day. Ask yourself questions and let the answers stew. Draw diagrams, write poems, look at paintings somewhere, read books, muse.

The “Micro” comments will be easier, if you agree something needs to change, change it.

You may have to go back to “the drawing board†in order to try something out. There’s no way to make something for the first time that isn’t, at some level, a risk. Sounds obvious, but it is hard to put new ideas/material in the middle of a work you have been laboring over. There is, however, no other way. You have to experiment, see what works, be willing to get it wrong.

4) Once you think you have something that might work, don’t second guess yourself, try it!

5) Keep in constant dialogue with yourself. Do not change what does not, to your way of seeing, need changing. Do not assume that other people’s suggestions will always be the right ones to address a problem. Identify the problem underlying the suggestion and see what the “critter” inside has to say about solutions.

|

| Catherine Howe, (detail of a work from the series, “Klytie”, 2007), oil/canvas 52 x 48 in. http://web.mac.com/catherinehowe/site/home.html |

Portraits of a Crit

By Catherine Howe, instructor at the Academy

It was Sunday, 3:30 pm, December 12, the third and final day of Mid-Year Critiques at the Academy. I was sick at home, but instead of just thrashing about in a feverish “As if I could BE there” sensibility, I thought I would share some glimpses of the “Crit-ers” and the “Crit-ees” from the first two days, along with some gems I jotted down before I became senseless with flu.

A stellar cast of “Crit-ers” participated, encouraging the students and sharing critical feedback essential to their progress through their Thesis projects. Wade Schuman, Lisa Bartolozzi, Patrick Connors, John Jacobsmeyer, Vincent Desiderio, Bob Simon, Bruce Gagnier, Kurt Kauper, Harvey Citron, and Margaret Bowland were among those who shared the following insights. See if you can guess who said what…

On painting with a system –

“…you have to turn a system into an aesthetic, it is like some contemporary jazz; it sounds like it is fun for them (the musicians), but it’s not for me.”

On “accuracy first” in the painting process – “Manet always started with an accurate underpainting before proceeding to simplify things. This accuracy fed his abstraction.”

On the Ineffable in art – “Rodin would say that the most important part of great architecture is the part no one talks about: the AIR inside it.”

An apt metaphor – “Please don’t give me something that is predigested!”

On habitat – “Criticism is in the past tense and painting in the present. An artist can be imprisoned with each mark, virtually painting within that cloistered place of certainty, or the artist can paint from an observatory, where sensation defies absolute description.”

On originality – “The artist must be a good parking attendant- it is usually best to back in while trying to avoid bumping into the cars of famous people.”

On bad television – “All the painting tropes have been absorbed by popular culture. The artist must consider that paintings now carry the detritus of everything else.”

On the monstrous – “You have to think how the parts relate to the whole, there must be an overarching idea or a system of integration or the result is nothing but an accretion.”

On depth of experience – “The painter should express ideas through the paint itself: you have to take me there and make me care!”

And, finally – “Cough, sniff.”

Art & Culture Lecture: Alison Elizabeth Taylor

|

| Security House, 2008-10, Wood veneer, shellac 93 X 122 inches |

Join us for the last Art & Culture lecture, given by contemporary marquetry artist, Alison Elizabeth Taylor. Well-known for reinvigorating the Renaissance craft of marquetry, or intarsia wood inlay, Taylor works in a medium once made popular during the unprecedented age of luxury of Louis XIV’s Court of Versailles. By choosing a medium that is typically associated with wealth and power to portray dystopian scenes of everyday life, Taylor creates a tension between the luxurious connotations of the material and a certain abjectness of the subject matter.

All lectures are free and open to the public!

Stay tuned to the blog for upcoming lectures in Spring 2011 including Donald Kuspit, Elizabeth Sackler and Phoebe Hoban.

-

Rosenberg, Karen. “Alison Elizabeth Taylor ‘Foreclosed’.†Art in Review. The New York Times. June 4, 2010.

- Kino, Carol. “An Artist Breathes New Life Into Renaissance Ways With Wood.†Arts. The New York Times. May 27, 2008.

- James Cohan Gallery

- http://www.artnet.com/artist/424152434/alison-elizabeth-taylor.html

Put some heART in your Holidays

A note from Academy President David Kratz:

Dear Friends,

Thanks to all of you who donated art to “Deck the Walls!” It’s thrilling to see such a wonderful show spring up almost spontaneously from everybody’s small works.

It’s such a great event. In addition to thanking all our supporters, “Deck the Walls” serves another purpose. It creates a level playing field that, because of the way it’s organized, encourages people to start collecting. Last year, many guests told me that they were normally too intimidated or indecisive to buy art but “Deck the Walls†made it so fun and easy that they bought more than one. Some literally left with armfuls!

Anything we can do to encourage people to start collecting, raises our own profile and supports the artists in our community. The fact that we also make it so much fun is a pretty nifty trick. But what else would you expect of a creative community like ours? In the spirit of the season, it’s a gift to all of us.

With warm holiday wishes,

David

Landscape Lenses

by Emily Adams (MFA 2011)

|

| Richard Diebenkorn, Ocean Park #92 (1976) |

Nearing the end of the fall semester, theses are being written and paintings are being refined for December’s mid-year mark. Last year, Sir Kenneth Clark’s The Nude was a required reading by this time. To be honest, I wasn’t so terribly thrilled about the book, but I recently finished his chronicle of Western landscape painting in Landscape into Art. In the book, he devises categories for ways in which landscape has functioned in painting over time, from medieval symbol to Renaissance fact to expressions of empirical naturalism and human emotions to a parallel to the act of painting itself (twentieth century cubism and abstraction). I can’t help but reread Clark’s book with an eye on locating the place of the human figure in all of his examples, and then look around at contemporary American painters for whom ‘landscape’ is a significant subject. Where is the human figure in contemporary American landscape? Could it still be high up in a building or flying machine? Or perhaps it has moved on to be present in the very fact of its absence?

|

| Mark Tansey, EC101 (2009) oil on canvas |

|

| Clayton Merrill, Falling (2002) |

| Vija Celmins, Untitled (Desert), (1971) Lithograph |

As I gather together my work from the semester, I’m beginning to realize that the absence of the human figure is at the heart of where I’m going. I’ve been trying to incorporate still-life and landscape to make paintings that are essentially about humans, without humans. In the meantime, I will continue to compile and analyze my list of contemporary-American-unpeopled-landscape-paintings. Studio work updates coming soon…

Art & Culture Lecture: David Salle

Don’t miss tomorrow night’s lecture by David Salle, an American painter who helped define the post-modern sensibility by combining figuration with an extremely varied pictorial language.

|

| David Salle, Angels in the Rain, 1998, oil and acrylic on canvas, 244 x 335 |

Major exhibitions of his work have taken place at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, Castello di Rivoli (Torino, Italy), and the Guggenheim Bilbao. In March 2009 a group of fifteen paintings were shown at the Kestnergesellschaft Museum in Hannover, Germany. That same year Salle’s work was also featured in an exhibition titled “The Pictures Generation” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, in which his work was shown amongst a number of his contemporaries.

All lectures are free and open to the public!

Next up:Â Alison Elizabeth Taylor, Tuesday, December 14, 7:30pm

Escape from Studio Lockdown

Dear Friends,

Perhaps you’ve had a nice lunch and are now back in your studio revved up to create a masterpiece. You’ve got your tools laid out, a chunk of time to yourself and lots of great ideas to explore, and then it hits – despair. How do you tell if your artwork is good or bad? Indeed, are you good enough to even call yourself an artist?

Everyone experiences these feelings and they are made worse by constant news or press about the successes of others. In the past, I might have tried to tough it out by chaining myself to my easel. But now I know it might not be such a bad idea to have my girlfriend go out with me for sushi.

One important thing I try to do is to occasionally return to a place where I felt happy, safe, and inspired to work. The following video interview took place on a recent visit to my original fount of inspiration, San Francisco.

Yours very truly,

Hilary Harkness