“You have to distinguish between things that seemed odd when they were new but are now quite familiar, such as Ibsen and Wagner, and things that seemed crazy when they were new and seem crazy now, like Finnegan’s Wake and Picasso.” – Philip Larkin

|

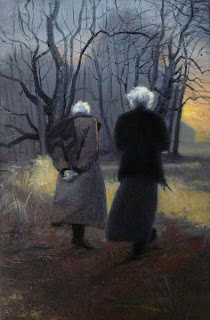

| My painting, Andrew Wyeth and Odd Nerdrum, inspired by a photograph found in the studio. |

When I first came across the work of the Norwegian master Odd Nerdrum, I was in my studio during the summer following my first year at NYAA. I had just recovered from the culture shock of moving from rural Georgia to New York, never even having visited the city before. I had grown up in a trailer park, had experienced poverty and struggle, and had finally paid my way through college between three jobs and scholarships. I had escaped, though I never thought I would end up in New York. I had never in my life had access to museums such as the Met, and for the first time I could see the Old Masters in person. It was indeed a life altering experience. The incredible technical and theoretical training I was getting at the Academy gave me a newfound ability to understand these masterpieces from many different perspectives. In my mind, I had already achieved success.

|

| Part of Odd’s collection of casts and sculptures. |

I bought both of his large books and memorized every detail. I went to see his exhibition at Forum Gallery and started experimenting with his heavy herringbone linen, but I just couldn’t seem to crack the code. People told me horror stories about his vast temper and cult like students, stories of them wearing nothing but animal skins and living some kind of crazy ascetic lifestyle on the Norwegian coast. So I just forgot about the whole thing and concentrated on my immediate situation. I was graduating soon, with the burden of student loans on my back, an overpriced apartment in Brooklyn, and I was in desperate need of a job.

Luckily, a friend of mine was working as a painter for Jeff Koons and set up an interview for me. When I got the job I was thrilled, but after a year and a half of long hours and overtime I found that I was no longer painting for myself and was just making ends meet. I learned much (mostly about the Art market), but all my energy went in to Jeff’s work. Though it was a good stepping stone, I could not see myself working there for years, so I finally decided to take the risk and I sent Odd a letter. When, a few months later, I learned that I was accepted, I had a feeling of both elation and trepidation. I was elated because I knew many people had been rejected, but still I had no money saved up and I had student loans to pay off. This was not a practical decision. Of course, that hadn’t held me back before. The feeling only slightly lifted when I finally arrived in Norway, jet-lagged and bleary on March 1st , to find three feet of snow on the ground and even more swiftly falling. I couldn’t see ten feet in front of my face, but through the eddies I could barely distinguish a car waiting for me, and standing beside it, a tall, imposing figure wearing a long double breasted black coat and a shock of hair – writhing in the wind and white as the snow. This must be Odd Nerdrum.

|

| The Studio |

As soon as I entered the car, he began to drill me with questions, the first of which was “Why do you wish to study with me?” In my exhaustion I somehow managed to answer him coherently, then I collapsed on the bed as soon as his wife, Turid, showed me to my room. My first thought upon waking the next day was, what have I gotten myself into?

It turns out that what I had gotten myself into was one of the best choices I have ever made in my life. I soon discovered that Odd was not only a masterful painter, but also a very kind man with a quick wit and an enigmatic personality. He holds a vast knowledge of art history, philosophy, literature, and technique, all just as bottomless as his sense of humor. And yes, he is very eccentric, but quite open-minded. (During my first week there, he called me into his studio and asked me to tell him what was wrong with his painting. Then he actually did what I suggested!) I was not required to wear animal skins and paint post-apocalyptic scenes. I didn’t have to slave away as a studio assistant, grinding pigments by hand, stretching canvases, and modeling. Yes, I did have to do these things sometimes, but most of my time was available for painting and learning. After six weeks in Norway, Odd invited me to study with him for a year in Paris: an invitation I couldn’t refuse. My wife and I moved out of our apartment, put our things in storage and ventured onto the plane. In Paris for the first time, I went to the Louvre, Le Petit Palais, the Rodin Museum, and many galleries with Odd; all the while debating everything we saw. I recall fondly the time we were kicked out of a Scandinavian run gallery in the 4th arrondissement. The owner chased us out screaming something about “Nazi-Kunst”. Apparently, they take Clement Greenberg very seriously in Finland.

Watching other students struggle to understand what he was trying to teach them, it dawned on me how many invaluable lessons I had learned at the Academy. Everything from aesthetic theory, anatomy, to historical techniques quickly sprang to memory and enabled me to grasp what he was demonstrating. Without this education, without these tools of analysis, I would perhaps have missed the deeper relevance and might have ended up going no further than a failed mimicry of his techniques.

Beginning with my first step into the Academy in 2005 and culminating with a year of study with Odd, my work has improved vastly. My dream of being a self-sustaining artist, once impossible, is now a reality. In the process I have made many great and long lasting friends, not the least of which is Odd himself.

|

| “Goliath Conquered” In the studio with a large canvas made straight and taught by an elaborate system of braces |

Odd once told me how, when he was about my age, he met a great American painter: a mentor. Odd felt that this man was one of the greatest artists to have lived and esteemed him along with the Old Masters. One day, he was leaving an exhibition in Philadelphia to find a limousine waiting for him outside. The driver informed him that the car had been sent by this artist and inquired if Odd would like to meet him. Odd accepted with surprise, and when he arrived on the farm, Andrew Wyeth and his wife were there waiting for him with glasses of champagne. They talked long through the night and there began a deep friendship, carried by letters and infrequent visits across the decades. Wyeth had just died when I met Odd, and it was very hard on him. He spoke of all the wealth the world lost when Wyeth passed on. And sitting there with Odd Nerdrum, before his paintings, thinking of his friendship with Andrew Wyeth, I felt a deep loss. I imagined myself at Odd’s age, mourning on the day when he will sadly, and inevitably pass. But I also felt a stirring hope. In this connection there was something. There was a taut string extending from me to Odd, from Odd to Wyeth, and connecting me through them back into the vanishing past. I sensed the similar connections I had made while studying with Steven Assael and Ted Schmidt, still vibrating within my chest. And in the accumulated vibrations of all those thin strings stretching across the ages, it seemed I could almost hear the distant voice of Rembrandt himself, as if whispering into a paper cup at the other end. They may have died, but their voices live on: faintly, but eternally.

Scott, Richard T., “The Odd and the Crazy.” ArtBabel. August 23, 2010 03:20 PM. http://artbabel.blogspot.com/2010/08/odd-and-crazy.html . October 11, 2010.